“It almost feels indulgent to be discussing the nature and the structure of the public market when the economic roof is falling in. But we’re going to anyway, right?” Paul Miller said wryly before diving into why he believes the Johannesburg Stock Exchange has become a shadow of its former self.

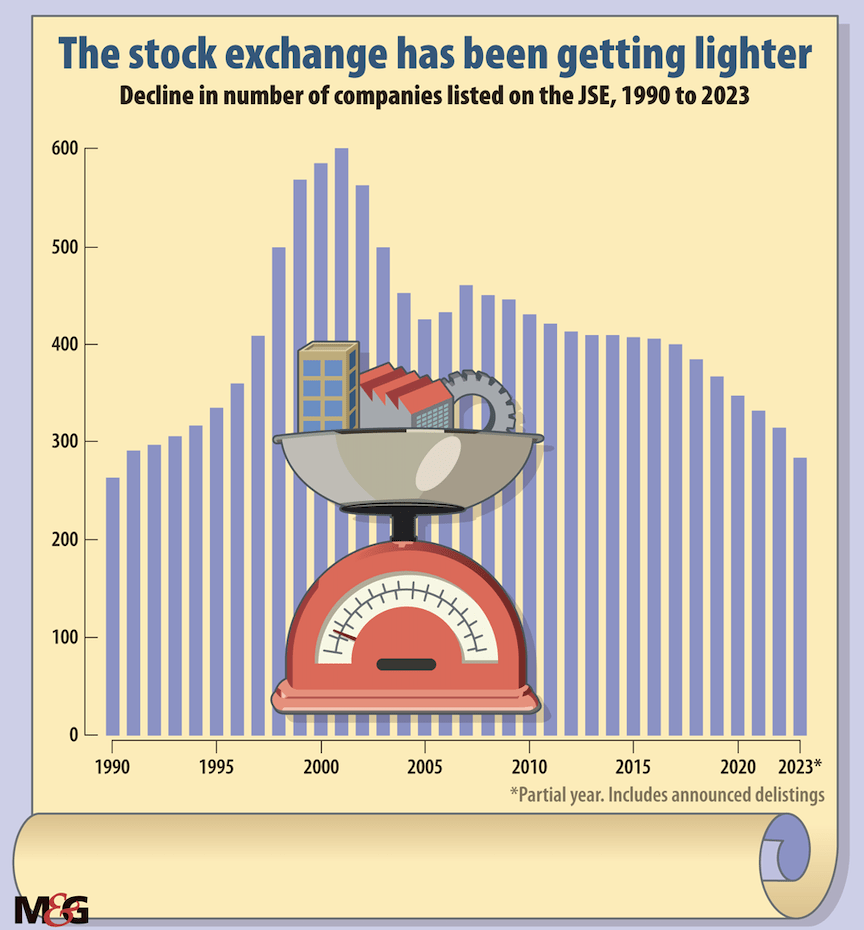

Miller is the chief executive of mining consultancy AmaranthCX, which maintains a database of all South African company listings and delistings going back to 1995. Between 2015 and 2022, South Africa’s public market was averaging about 25 delistings a year.

The exodus of listed companies from the JSE has been a topic of discussion among traders and analysts for some time now. The JSE has also struggled to attract new players, leaving it to be dominated by its biggest listings — the influence of these mostly old outfits, many of them foreign companies, becoming more and more powerful.

The result, according to experts, is that South Africa’s public market is slowly losing touch, only serving a very narrow section of the economy.

Large and liquid

Between 2002 and about 2007, Miller — who was an investment banker and an approved sponsor on the JSE — enjoyed something of a purple patch when mineral rights were freed up and individual listing regulations were relaxed.

“And, of course, it was wonderful until the financial crisis took us off at the knees. But it was enormously personally fulfilling for me. And I just loved being in the white-hot heart of capital raising in the free markets and getting stuff done … And it was all because public markets worked for us,” Miller said.

“But something went wrong.”

A decade later, when he was brought on board to help get Alphamin Resources listed on the JSE, Miller faced rejection after rejection. Asset managers and mining analysts either cancelled meetings or refused to meet at all.

For Miller, the argument that the JSE is at fault for its listings crisis — that it is too expensive and that its regulations are overly onerous — is too simplistic. “So, if it’s not the JSE, which sits between capital and companies that need capital, then the problem must be in the structure of how we manage our savings in South Africa.”

The R9 trillion or so in savings collected in South Africa, Miller noted, is largely managed by 10 institutions, making for massive concentration. As the business has become more institutional, private investors (who invest directly with stockbrokers) have been left out in the cold.

Miller tracks this change in the fortunes of private investors to the Jacobs Committee report of 1992, which levelled the playing field between asset managers and insurance brokers, but ignored retail. “We have institutionalised savings,” Miller said.

“And by institutionalising savings we have created a monolith that only invests in the large and the liquid.”

Miller has previously argued that this bias exists because the regulators are implicitly beholden to the large institutions. “Every lawyer, every policy expert, every lobbyist makes their living by working with those 10 institutions in some way or other,” Miller said.

“Now, take it one step further. Those same 10 institutions are the majority shareholder in the JSE and they are also the majority customer of the JSE. So, there’s a massive inherent conflict of interest between the interests of a dynamic, active public market — particularly at the smaller end — and the interests of our institutions to dominate.”

Moreover, in other economies where the middle class is bigger, there is more of a voice on the side of direct investors.

South Africa’s public market, according to Miller, has stultified.

As hinted at in his initial statement about discussing the JSE’s shortcomings seeming indulgent, the financial market is somewhat divorced from what happens in the real economy. This gap becomes more pronounced when the public market is dominated by a small group of companies, a number of them foreign-based and in the tertiary sector.

Withering away

The JSE’s top 40 represent 80% of the total market capitalisation of all its listed companies. In this list of companies, there is barely a newcomer in sight, trader and analyst Simon Brown points out.

“Who are the whippersnappers on the JSE in the top 40? Discovery springs to mind, but Discovery has been listed for 25 years. Whereas, if I look at the Nasdaq, they’ve got Facebook, which has been listed for a decade … We’ve got Naspers. Our banks are all 100-plus years old.”

Miller has previously also pointed out that foreign companies listed on the JSE account for more than 60% of the total market capitalisation of the bourse. “What we have done is we’ve converted 60% of our JSE to foreign companies, so that there are no jobs here for investment bankers or investor relations specialists,” he said.

“We’ve allowed it to wither … We are giving up one of the fundamental advantages South Africa has had for a century. We are letting it fade away. And the people responsible are not even fighting for it.”

For its part, the treasury said, it rigorously formulates policies to enhance South Africa’s attractiveness, adding that it is actively addressing regulatory and policy hurdles to new listings. The policy formulation process, it said, is pursued without fear or favour.

The JSE has maintained that listing activity is driven by market sentiment and the country’s macroeconomic conditions.

According to Sam Mokorosi, head of origination and deals at the JSE, the local bourse has made a concerted effort to make listings easier and attractive “without compromising on investor protection”. Last October, following a public consultation process, the JSE proposed amendments to its listings framework aimed at boosting competitiveness.

“Most delisting trends are cyclical, given the JSE’s focus to address the current challenges and concerns raised by the market, we do believe that we are doing everything in our control to ensure a robust capital market,” Mokorosi said in response to questions from the Mail & Guardian.

Despite the delistings, the JSE’s total market capitalisation continues to rise, Mokorosi noted. There are 297 companies listed on the JSE and an overall market cap of R 21.8 trillion.

Meanwhile, a newcomer in secondary exchange A2X has stepped on the JSE’s turf, attracting brokerages with its far lower costs. The JSE makes a lot of its money through transactions and, if its volumes start to drastically decline as result of competition from A2X, the incumbent could be in trouble.

Speaking to the M&G last week, A2X chief executive Kevin Brady said that the immediate focus of the secondary exchange is to grow its market share, increasing its listings and adding more brokerages. Between April 2019 and April 2023, the combined market capitalisation of A2X listed securities has grown from around R2.5 trillion to almost R9 trillion.

A2X has also set its sights on becoming a primary exchange.

“However, we are very conscious that South Africa’s regulatory environment is outdated. And, at this point in time, it does not really support a competition exchange like ourselves,” Brady said, noting that the regulations don’t allow for the transfer of listings from one exchange to another.

In this case, A2X may be able to catch some minnows but will struggle to persuade bigger companies to delist from the JSE and list with the newer exchange. Notwithstanding the regulatory barriers to A2X becoming a primary exchange, the competition has been enough to make JSE shareholders antsy.

Deregulate

The Lowenthal family have been JSE shareholders since the bourse was demutualised and listed. In separate conversations with the M&G, the Lowenthal brothers — Martin and Howard — said the JSE is allowing A2X to eat its lunch.

The pair have been vocal critics of the JSE’s onerous listing requirements. “We have deep emotional ties to the JSE … The problem is that the JSE seems to have rejected the idea that it should be a platform for new companies. They are even allowing some of their trading to go to the other exchanges,” Martin said.

“To me, every trade that they lose is a disaster.”

For the Lowenthal brothers, the JSE has to be the marketplace for companies to raise money and for investors to take stock. But, according to Howard, the JSE has instead become something of a watchdog, only listing what it believes are quality companies.

“Don’t tell me about quality companies. We couldn’t list a thousand venture capital companies and lose as much money as Steinhoff, EOH, Tongaat Hulett … You can’t regulate poor accounting. That is the job for the auditors and the regulators,” Howard said.

“Just look where we are. We’re on the southern tip of Africa. What do we need all these rules and regulations for?”

South Africa’s public market is broken and is serving a very narrow function, Martin said. The public has largely been left out, because investors cannot commit capital to growing companies. This is as institutions have favoured the top end of the market.

“It’s crisis time. They have totally lost their way. Their volumes are dropping. The number of listings is dropping. So, clearly, the current business model is not working and they have to make some changes,” he said.

“We have seen virtually nothing in the last five or six years. A little bit here, a little bit there. There should be a top to bottom overhaul of the JSE, from every aspect — from a listing aspect, from a trading aspect, from a personnel aspect. It needs a total overhaul.”

The M&G reached out to some of the JSE’s largest shareholders, namely Allan Gray, Ninety One and PSG.

Both Allan Gray and Ninety One suggested they have engaged with the JSE on the issues hindering listings. Sumesh Chetty, portfolio manager at Ninety One, said the JSE is well aware of the issues and working on them as a matter of urgency.

At the time of writing, PSG had not responded to the M&G’s request for comment.